There is an hour in the early morning when every beast in Burkina Faso takes to howling. The noise is deep, cacophonous, and urgent. It is the braying of donkeys and the wailing of dogs on top of a chorus of goats and the jealous shrieking of roosters. Pigs join in for good measure, and so do the birds, all participating in an unconventional harmony that rouses a lazy yellow sun from over the Solenzo’s Lycee.

I wake up during this hour, for no other reason than because I feel guilty letting two full hours of moderate weather go to waste. Moments after I open my eyes, the call to prayer from a dozen different mosques picks up, complimenting rather than competing with the church bells, all calling worshippers to drag themselves through the early morning darkness and take to their knees in thanks for another day.

This is my alarm clock. It is way of waking up that lends itself far more to lucid dreaming than alertness, but somehow I manage to drag myself out of bed every morning and go for a run, returning half an hour later with a self-congratulatory air and four new articles of clothing to wash. The girls have already been up for an hour and a half of course, and wrapped in pagnes and winter parkas they go about the Center busily completing their long list of morning chores. They greet me (far too enthusiastically for the early hour) as I draw water from the pump, and fly ahead of me balancing basins of water on their heads twice the size of the buckets I am carrying.

The girls and I began planting the nursery for our community garden in November. Here they are replanting our cabbage seedlings.

I have 30-something little sisters (more keep coming), some of which are at the Center to attend one of Solenzo’s many schools and some of which take classes and learn exclusively at the Center itself. This latter group of about 20 girls are the ones I work with primarily. As goofy and adolescent as they are, they still attack every day with a tireless work ethic that simply baffles me. As a result, their backs are stronger than mine, their biceps bigger, their stamina greater and their recovery times shorter. They can pound corn into the fine powder used to make to and prepare an array of sauces. They can carry 20+ gallons of water on their heads without spilling a drop and break up dry, unyielding earth with heavy pick axes to lay fine seeds, all while manipulating a phone with the other hand. Some lazy afternoons I’ll wake up from a nap to find them huddled together in the central hanger, teasing each in one language or another and manipulating tufts of hair into neat, expertly executed braids and twists. This time is one of the only breaks they get from their duties, which otherwise consume them from about 4 in the morning till past 9 at night. The Center for them is at once a hair salon, a garden, a kitchen, a classroom, a dormitory, a playground, and temporary home that gives them little respite from their duties in their respective villages.

The girls dance at the the Center's opening mass

Each one of my little sisters has come to the Center for a different reason, but the nuns have a very particular idea about how they will act once they are inside. This became apparent to me when Sister Elizabeth asked me to type up the rules and regulations for the Center. It began with these words, which are intended to exemplify the Center’s values:

Fraternité Travail Discipline

Before going on to state a long list of proper behaviors such as respecting the property of the Center and committing yourself to your duties, the document noted that the goal of the Center was to create an environment for young women that would prepare them for their lives as mothers and wives, emphasizing these values of fraternity, work, and discipline. Fraternity, work, discipline. Each word seemed perfectly inappropriate for me to apply to a teenager. I prodded the nun a little, originally asking if she’d let me change the word ‘fraternité’ to ‘sororité,’ which apparently isn’t even a word in French. But this didn’t bother me as much as the aspirational statement, which stated that the Centre Marie Moreau was intended to prepare young women for their roles as wives and mothers. I see the Center and places like it as golden opportunities to take the marginalized 50% of Burkinabe society and raise them up to aspire to be anything they choose. Instead, the mission statement aspires to teach them nothing more than what they could have learned staying in their villages and not attending school? It is like stumbling upon a stretch of rich, fertile land and then deciding not to grow anything.

Leontine in the garden.

Do not misunderstand me: Being a wife and a mother is no small role to fill. In fact, for many women with or without careers from every corner of the world, it is the most challenging, rewarding and important job they hold. I know that I personally look forward to it myself. However, I have something that these girls are not as fortunate to have, and that is the ability to make autonomous choices about my future based on an extensive and meticulous education. Despite the endless list of domestic skills these girls already possess, many of my little sisters have severe trouble with is reading, writing, speaking French and thinking critically. They struggle to follow directions they are not familiar with and struggle to innovate, problem solve, or be leaders among their peers. These are part of a long list of aptitudes that are largely a pre-requisite for interacting with the world beyond one’s own village, and the relative absence of them in the girls I work with (or at least, they’re reluctance to demonstrate them to me) stems from a multitude of reasons. Only one of these reasons I have come to find, is the fact that many of the girls don’t have past a third grade education level. I have been privileged to take these skills for granted for most of my life, not just because I had access to excellent schooling but also because I had an entire team of adults behind me telling me I could be and do anything I wanted to. Telling me at every stage of my life that I had a choice.

Flavienne and Ginette at opening mass

But in a culture where the man is always the head of the household, always the breadwinner, and women are expected to serve a certain role, where exactly does all of that scholarly critical thinking come in? I have sat with groups of Burkinabe men on multiple occasions and been told that women don’t have their place in politics, that they must always be subservient to their husbands, that they have no right to decide how many children then want to have. I have been told that men have a right to women’s bodies as they choose, and that educating women leads to high divorce rates and moral depravity. I have been told that women already have too many rights, and that no man wants a woman that would argue with her husband or who earns more money than he does. And I have seen, first hand, sixteen-year-old girls leave the Center to get married to much older spouses so that they can start having children before it’s too late. So when I come at then waving all of my Western ideals and telling them to stand up and be confident, I can only thank them for humoring me.

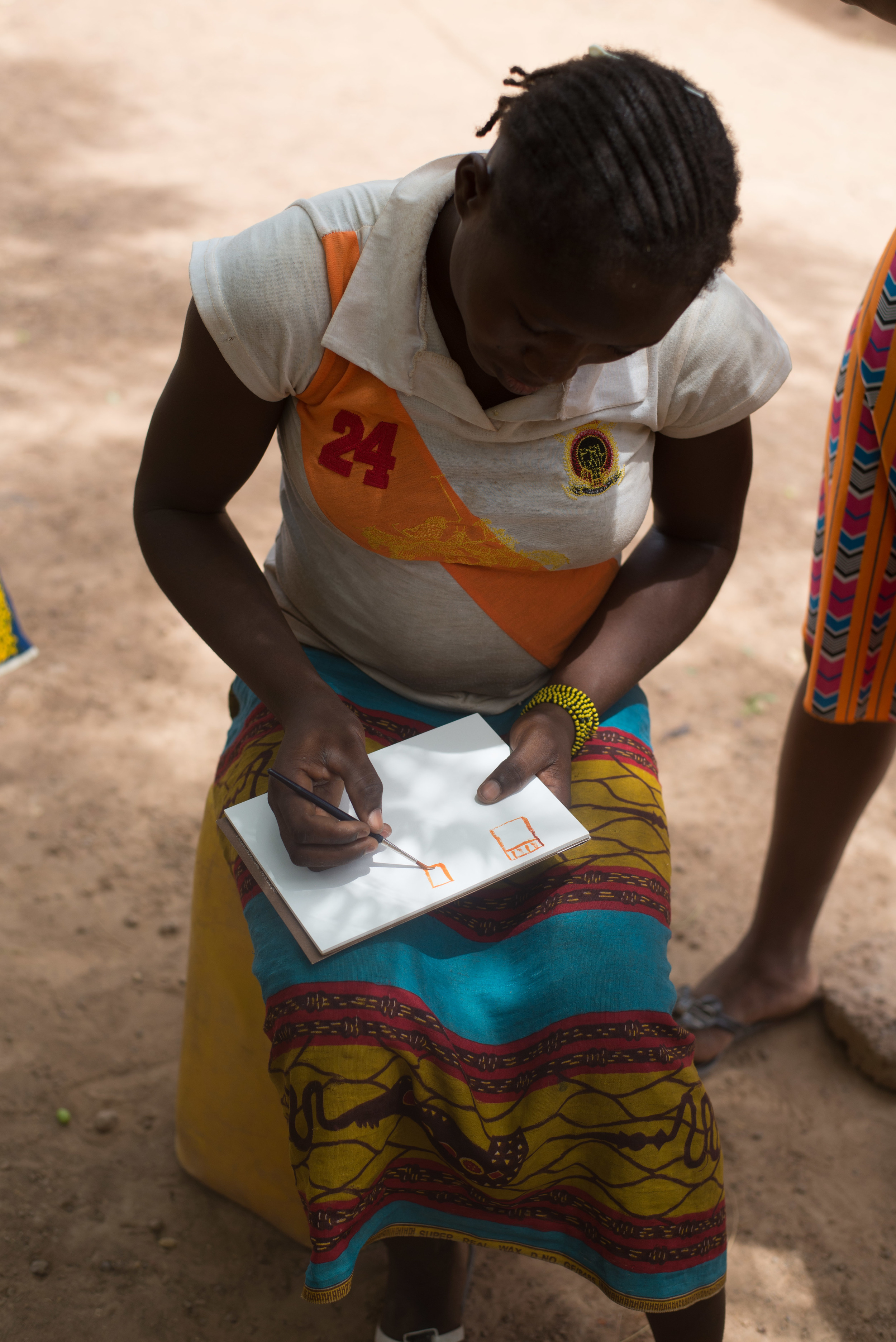

Monique in the garden.

For a group of girls that will likely grow up to marry and become mothers, what they need is the ability to make their own money to support their family, a way to keep food on the table and clothes clean, and a way to accept a life of never never resting. Reading, writing, speaking French, leading discussions and thinking critically about Burkinabe practices or traditions are not necessarily skills these girls see themselves needing in their immediate future, and it seems the nuns don’t see that they will either. Without high school educations or any kind of equivalency, they are highly unlikely to augment their positions in society such that the more Westernized world of Ouagadougou and Bobo-Dioulasso should concern them, so who am I to tell a group of already disenfranchised young women that I want them to focus on skills they may never use? What they need, effectively, is fraternity, discipline and work.

If you are like me, however, you have already seen the flaw in this argument: Are we to prepare our children for the world we live in or the world we want to live in? The answer, of course, is both. I’m not just here to bolster what is already being done by adding to the list of artisanal and income generating skills that will help these girls create financially stable lives for themselves. I’m also here to push them a little to look beyond that, to peek over a socially constructed wall that, little by little and with many helping hands, these young women are climbing. If I can become a mentor and a source of support for those of my little sisters who decide they want more choice in their lives, then I need to be ready to do everything possible and culturally appropriate to get them there. So, despite losing out on convincing the nuns to insert sororité into our mission statement, I did get them to agree to add one more word: Creativity. And with those four words nicely framing my goals here at the Center, I sleep a little easier every night, ready to wake up to that strange, four-legged symphony.